I've been intentionally holding back a part of our summer that is not inconsequential until I was ready to start telling it. Today is that day. I'm not telling it because it is the most sensational story I could tell, but because I want to tell the truth and this is bound to be a part of the truth of our time in Vermont.

On July 3rd I got home from class at 12:45 and Bryan was talking with a young man in front of the yurt. Something seemed slightly amiss with the conversation, based on Bryan's demeanor, only visibly in the tiniest way that you can see in those you know ridiculously well. I walked up and the man, we'll call him Jake, finished his thought and I introduced myself. We shook hands and I tried to get caught up in his story. Without going into too much detail, he basically had come to Bryan the host to let him know he wouldn't be able to pay for his campsite and he wanted to talk with a ranger about it.

Since the rangers are rarely there, Bryan and I just said we'd try to reach one and would send someone his way when we could. Meanwhile, he had told Bryan that he was homeless, hinted that he was hungry and intended to try to fish for food, talked about how he got dropped off by a woman with five terrible kids who swear and are only ten and are embarrassing to be around, was staying with a friend but had to leave during the day and basically had nowhere to go. In short, he came off as really desperate. We assured him that we'd do our best to get a ranger for him. He walked away with a look of disappointment on his face that we couldn't quite read.

In my head since that day, even an hour later, I tried rewriting that moment, forcing it to be kinder, more generous, or just different.

Bryan and I went into the yurt and both had alarm bells going off in our heads. While he didn't seem like he was on drugs, posing a threat, was violent, etc. we just kept saying he seemed so

desperate. We were concerned. We were worried that we had made plans to be away from the campground most of the afternoon and then late into the night. We feared for the safety of the dogs and our things. We worried that he was casing us out. We felt paranoid. He was a nice guy, but that desperation coming off of him in waves scared us. We know that people who are desperate will do anything, and in some ways, you can hardly blame them because they feel like they're trapped and that was how he came off.

We asked each other if we should have given him some food. We had food in the yurt that certainly would have helped. We wondered what to do. We wondered if we should radio the ranger station. Or go into town to call them. Or offer to take him to the free campground. Bryan went back and told him about the many free camping options available to him around the area. He told him that he knew about those, having grown up in Goshen, but hadn't felt like going that far. He had intentionally chosen to be dropped off at a campground that he knew wasn't free. We certainly were not going to send him on his way down the road and tell him he couldn't stay, but we left the yurt and worried about it all night. We saw him later that afternoon, maybe around 1:30, walking back to his site with fishing pole in hand and fishing vest on. That was the last time I saw him. Bryan headed into town so he called the conservation officer for our region who was on his way to the Finger Lakes, so planned to send another officer up in the morning.

I've wondered since that day if we did the right thing. I wondered it that night and the next morning. I wondered if his presence, his desperation and need were some sort of test of human kindness and Bryan and I had failed it by not offering him food or being more generous. Don't get me wrong, we were not unkind to him, but we certainly could have done better. Had we known what was to come, we certainly would have. At the same time, and this is what friends and my mom said when I told them, I know that we live in a world where sometimes you have to protect yourself first. Unfortunately, both Bryan and I were afraid of Jake and his presence at the campground. Unfortunately, we live in a world where I have to fear that I might be a victim if I put myself out there too much. I, right or wrong, feel nervous if I'm at the campground alone because I am a woman. Neither Bryan nor I spoke of this at the time, but I think we both instinctively didn't want to do too much for him because we didn't want him to come back when I was alone. We have to deal with that instinct. Bryan was working at the time, so that meant that I was alone at the campground at night and I was afraid to make myself too approachable to

anyone at the campground.

The next morning two national forest officers arrived to talk with us and then go approach Jake and see if they could help him make a plan. We talked in somewhat hushed tones because Jake's site was close to our own and we didn't want to offend him. We explained all of the above, that we had been nervous, but that he seemed like a nice guy. They asked the questions you might imagine, like if we thought he appeared to be on drugs, or if he seemed violent. We both paled a little when they asked if he said anything about wanting to hurt himself. He hadn't.

With our information, they headed over there but Jake wasn't there. They checked back in with us to see when we'd last seen him. Bryan had seen him at his site at 3pm on the 3rd. It was now around 11am on the 4th of July. We left to go for a hike and when we came back, there were more police cars and one headed up there. We worried about him having a record or a warrant out for his arrest. What if they arrest him and he seeks retaliation? What if he is violent? They came back and let us know that something in his tent indicated that he might have been suicidal and they were going to launch a search and rescue. We were absolutely sick about it, blaming ourselves, wondering why we hadn't been kinder, been more human instead of more suspicious. Why hadn't we been better?

Several officers came and took down our information, had us retell what we knew, the information he had given us. The two national forest officers checked back in with us, asking about fishing poles, telling us he had a bow in his tent and that they thought he had taken pills, taking the timeline again. We prayed that they would find him alive and that he'd recover and get some help, but they didn't seem hopeful. They brought dogs in to assist with the search.

In the meantime, Bryan had to go to work. Off he went on his bike, and there I sat, trying to write a paper and keep my mind off the mayhem around me. An ambulance pulled up and I feared the worst. Detectives came. More police. The dogs walked through the campground and they were canvassing to start a broader search. About an hour later, I heard, not 30 feet from where I was sitting, "He's here! He's alive!" In between our site and his, Jake was found. They yelled his name, asking what he had taken, talking to him, saying his name, telling him to stay with them, and seconds later, several men carried him off to the ambulance and he was gone. I sat down on the floor of the yurt, grabbed the nearest poodle and cried, praying that he'd pull through.

Many of you know that suicide hits a little close to home for me, making this event perhaps more emotionally charged than might seem appropriate for some guy I didn't know (but maybe you can understand how much you feel tied to a person when you're present at their traumatic moment). That, and the fact that Bryan and I may have been the last people he talked to, let alone reached out to, probably hoping we would help him out. I had to process, whether you can argue that the situation warranted concern or not, whether you can argue that our concern caused us to call the officers in, and saved his life, I still feel like we failed him in some way. In my assessment of the situation, I can't help but believe that he was trying to make his way to our site, to get help, when he collapsed. I wish we would have been home earlier, awake longer, more aware.

The officers who had taken the call came to our site maybe a half hour after the ambulance left. I shook the first officer's hand and told him he had done good work today and thanked him on our behalf. He just shook his head and scoffed at the fact that he had been

right. there. the whole time. Probably a dozen officers had their backs to him for at least an hour and

no one saw him. He was in between our campsite, not hidden deep in the acres and acres of National Forest they were prepared to search. I assured him that I felt the same way, that had I just walked that way, I might have seen him. He told me he was alive and they hoped he'd recover, but he didn't necessarily seem that positive. He said we had done the right thing by calling, that it was because of us. When I told Bryan that, he said what I had been thinking, disgusted with ourselves, that we hadn't called because we were worried about

Jake, we had called because we were worried about

us. That's a hard pill to swallow.

That was the fourth of July and we didn't hear any follow-up until this Wednesday. I had to watch some friend or family of his come to the campground in the early morning hours on the 5th and pack up his tent and his belongings not knowing if they were doing so with his death or his recovery to bear and I couldn't help but be disgusted that no park worker felt the need to come and speak with us about what had happened. When the deputy came by on Saturday, she wanted to tell us we had done good work that day. We ducked our heads and thanked her, but she couldn't tell us if he was alive or not, she hadn't heard. I know in that job you'd have to compartmentalize, and you'd have to become hard to the stories you come across, but I couldn't believe that they all seemed to think the story ended when it left their hands. When the ranger came to our campground this Tuesday, he didn't even bring it up. I had to ask if Jake had lived and he didn't know. I looked him in the eye and said, "I need you to find out for me. It matters." He called me the next day, leaving a message that all the reports he had seen said that he arrived at the hospital and was stabilized.

We've been thinking of him, thinking thoughts of recovery, believing that hitting rock bottom might help him begin to climb out of it. I've got to believe that he'll get help. Yesterday when Bryan picked me up, he had had a visit from him. Jake had come back, fishing pole in hand, to apologize. Bryan couldn't say what he was apologizing for, but he just told him he hoped he would get well and that things would get better and that we were just glad he was okay. He wanted to know where they had found him and who had found him, and he said they had found cocaine in his blood, he didn't know how it had gotten there, and that that was likely what saved him. I don't know what to make of that, but I know it doesn't really matter. He said he was getting treatment now and that he hoped that he'd get better.

I've been wondering since the day of the search and rescue if maybe the reason we were so unnerved by Jake, despite the fact that he was nice, was that he was just a little closer to death than humans should be and we could sense it. I don't know if I can explain it well enough to make you understand, but Bryan did, so I'll try. I think people who no longer want to live (however temporary that inclination) rub up against death and it changes them in some way, unnerving those who are still in the land of the living and it's why we were afraid and ultimately, why we called. It doesn't provide absolution, but it's something.

Anyway, every week they show a movie on campus, typically a horror movie because there is a horror class (I was too afraid to take it when I saw the Japanese version of The Ring on it. Remember when Katie had that long black hair, people? I'm still sort of afraid she might pretend to be that girl again). This week was The Shining which is the single greatest horror movie of all time and one that my parents let me watch when I was way too young. No wonder I thought my room was haunted for awhile growing up. They show the movies in the barn, projecting the films onto the wall and everyone sits around drinking beers and looking afraid. It's great. Evidently last week a bat was flying around in there during the film.

Anyway, every week they show a movie on campus, typically a horror movie because there is a horror class (I was too afraid to take it when I saw the Japanese version of The Ring on it. Remember when Katie had that long black hair, people? I'm still sort of afraid she might pretend to be that girl again). This week was The Shining which is the single greatest horror movie of all time and one that my parents let me watch when I was way too young. No wonder I thought my room was haunted for awhile growing up. They show the movies in the barn, projecting the films onto the wall and everyone sits around drinking beers and looking afraid. It's great. Evidently last week a bat was flying around in there during the film. After that we headed to Shelburne and went to Folsino's Pizza which shares a building with Fiddlehead Brewery. We got a strange pizza with sweet potatoes on it that didn't work for us and got a growler of Fiddlehead's IPA. The pizza place doesn't sell alcohol, but they have chilled glasses so you can buy Fiddleheads growlers or bring your own drinks in and use their glasses.

After that we headed to Shelburne and went to Folsino's Pizza which shares a building with Fiddlehead Brewery. We got a strange pizza with sweet potatoes on it that didn't work for us and got a growler of Fiddlehead's IPA. The pizza place doesn't sell alcohol, but they have chilled glasses so you can buy Fiddleheads growlers or bring your own drinks in and use their glasses.

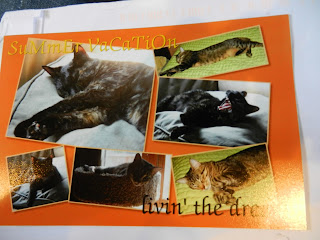

And if you think I've forsaken my schoolwork for all these shenanigans, you'd be wrong. Friday Bryan wasn't feeling well so after loads of Pepto Bismol, he just laid in bed all day and I did this:

And if you think I've forsaken my schoolwork for all these shenanigans, you'd be wrong. Friday Bryan wasn't feeling well so after loads of Pepto Bismol, he just laid in bed all day and I did this: